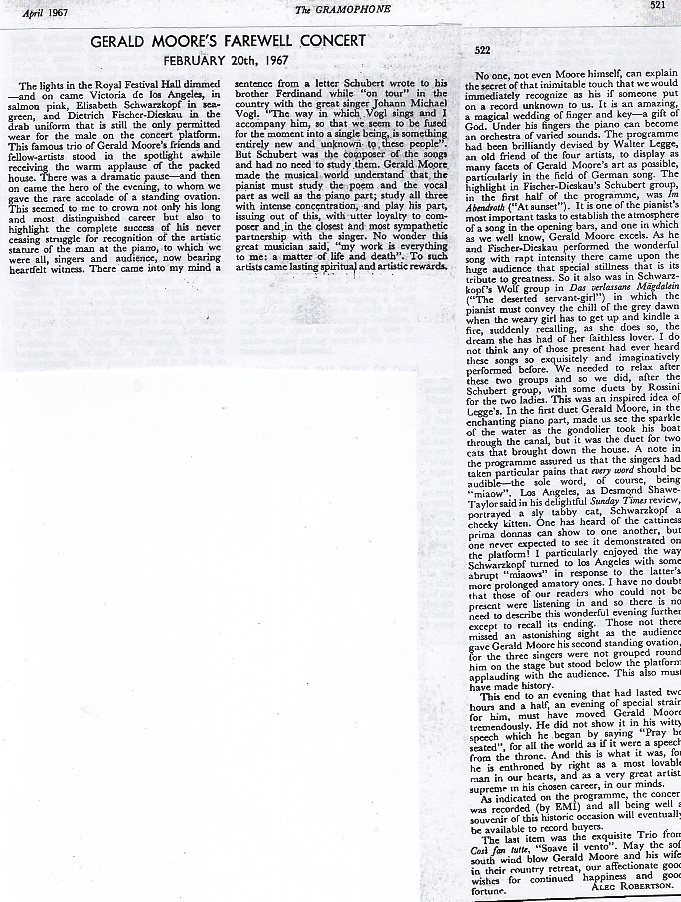

Zum Liederabend am 20. Februar 1967 in London

The Times, London, 22. Februar 1967

Farewell to the world’s greatest accompanist

Gerald Moore stoutly maintains that the first notice in The Times of a concert at which he played accused him of contributing "perfunctory accompaniments". Perhaps it may have seemed so at the time – a very long time ago, though his appearance makes one doubt it. The Times music columns always attempt to tell the truth, so we will not apologize to him at this late date, but simply declare that few of us can remember any occasion on which he has played less than magisterially, whether for the world’s greatest singer or for a modestly equipped débutant.

His long sustained position as the paragon of pianist partners (he does not like to be called an accompanist but at the risk of insulting him we will tell posterity that he was the greates accompanist of his day, and perhaps of all time) was affirmed on Monday in the Festival Hall when, to commemorate his declared retirement from the concert platform, Walter Legge assembled together the three singers with whom, Mr. Moore writes in his memoirs, he has most enjoyed working – Vicotria de los Angeles, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. They sang trios with piano (changing the text of one by Haydn so as to make it applicable to Mr. Moore – "O wollte Gerald nur weiter spielen", "If only Gerald would go on playing!"), vocal duets with one another, and groups of Lieder.

Most of these were so chosen as to throw the spotlight on the pianist: "Der Einsame" and others by Schubert in which the voice provides an obbligato to the strongly characterized melody and figuration and lively lilt of the piano part; Rossini’s duet, "La Regata Veneziana", with its glittering, agile ritornello descriptive of the dip and flash of the gondoliers’ oars; Wolf’s "Kennst du das Land" in which Mr. Moore, as so often in the past, demonstrated the superiority of the piano version to either of the composer’s orchestral transcriptions – unforgettably inspiring, this partnership with Mme. Schwarzkopf. But even in those items where the piano plays a subordinate role, and when the singers were exercising their virtuosity to the full, such as Rossini’s duet for two cats (virtuoso miaowing by Schwarzkopf and los Angeles), Mr. Moore’s artistry was descreetly yet inevitably intimated. Perfectly balanced partnership – this is Mr. Moore’s secret.

At the end of the evening he had the platform to himself, made a characteristic speech, full of dry wit and warm appreciation (it began "Pray be seated", since he had been given that rare accolade by British audiences, a standing ovation), and concluded, as we had all hoped, with the transcription which we hear him play on the radio every Sunday morning, Schubert’s "An die Musik". "Du holde Kunst, ich danke dir", the song ends – Gerald Moore, wir danken dir.

William Mann

Daily Telegraph, London, Datum unbekannt

‚Miaow’ duet in music for Gerald Moore

It can fairly safely be said that never before have two of the age’s most famous prima donnas collaborated in a public imitation of two cats – even in honour of their favourite accompanist.

Yet the Festival Hall concert in which Victoria de los Angeles, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau joined to offer their homage to Gerald Moore, included a brilliantly comic duet by Rossini with no other text than "Miaow."

The plan of the evening’s programme was pleasantly varied between the light and the serious, and the solo song, the duet and the trio. Each singer chose one composer for a group of solos.

*

Victoria de los Angeles’s Brahms songs includes "Sapphische Ode" and "Mainacht" and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf’s Wolf the wonderful, rarely heard "Kennst du das Land" and "Die Zigeunerin." Fischer-Dieskau chose such Schubert songs as "Der Einsame," "Im Frühling" and "Abschied" that displayed the special felicities of Mr. Moore’s playing.

The duets started with Rossini’s "Venetian Regatta" (incidentally another pianist’s showpiece) and continued with examples of the domestic, Biedermeier pieces by Schumann and Mendelssohn – not great, though often charming music and certainly period pieces.

The trios introduced Mozart – first the light-hearted domestic music of an earlier age and finally the trio "Soave sia il vento" from "Così fan tutte."

*

Imperturbable and benign, equally at home in lyric and farce, supplying for harpsichord or orchestra, but happiest of all in the occasion for the characteristic tone of his chosen instrument, Gerald Moore was unmistakably the hero of the evening.

This was perhaps the occasion which, more than any other, crowns with success his lifelong campaign for the accompanist’s right to be regarded as an artist potentially the equal of those whom he partners.

His final farewell was wordless but eloquent – a performance of the piano version of Schubert’s "To Music," by which he is known to an enormous number of music lovers.

Martin Cooper

Observer, London, 26. Februar 1967

Homage and farewell

We may all think we know what Gerald Moore has meant to our musical life, for many more years than most of us can recall. But I suspect that only the artists themselves, the raw as well as the mature, the ageing as well as the youthful, each with his own set of tensions and problems, can measure his full contribution to those countless evenings, some golden (my mind goes back to Elisabeth Schumann’s last recitals), some no doubt escaping disaster by a hair’s breadth, when he has been ‘at the piano.’ What, then, could have been more fitting than that three of the most distinguished singers of the day should have joined to pay homage to this miraculous perennial at his farewell concert at the Festival Hall last Monday?

The human voice is a disobliging instrument and, like every recital, the evening had its bumpy moments. But on at least two or three occasions it reached such heights that the heart could only stand still and gasp in wonder. The first of these came in Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s Schubert group. After songs in which he seemed to be having difficulty in wielding a great range of expressive nuances into a firmly drawn line, he suddenly in ‘Im Abendrot’ struck down to that profound inwardness, at once still and intense, which is one of his most remarkable gifts as a singer, and this Gerald Moore matched with a wonderfully concentrated accompaniment, full of the most subtle yet unobtrusive dynamic inflections. It would be hard to conceive of a greater rendering of a great song.

But one cannot breathe for long on such heights, and it was a brilliant stroke of programme planning (of which the whole concert could indeed stand as a model) on the part of Walter Legge to plunge us from this sublimity straight into the hilarious worldliness of duets from Rossini’s ‘Musical Evenings,’ sung with stylish gusto by Victoria de los Angeles and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Here a duet for two cats was a special hit, and Miss de los Angeles, in particular, achieved some startlingly authentic miaowing.

There were other refreshing musical sorbets in this long evening, notably some Mendelssohn duets, deliciously sung by Victoria de los Angeles and Fischer-Dieskau. But the most memorable moments of the second half came in Miss Schwarzkopf’s Wolf group. Casting aside the interpretative frills that can on occasion mar her singing, she plunged right to the heart of the unappeasable longing of Wolf’s miraculous setting of ‘Kennst du das Land’ and of the utter desolation of ‘Das verlassene Mägdlein.’

Wild abandon

These were deeply moving performances, and Mr. Moore, who can always be relied on to rise to the subtleties of Wolf’s piano writing, was in every way worthy of them. The wild abandon of the ritornello, ‘Kennst du es wohl,’ was superbly articulated. Even more remarkable was his ability so to shade the accompaniment to ‘Das verlassene Mägdlein’ that a shaft of light momentarily seemed to flicker over the music’s black despair, as the serving-girl stares at the flames she has kindled. It is at moments such as these that one becomes painfully aware of the gap that Mr. Moore’s retirement is going to leave.

Peter Heyworth

The Guardian, London, 22. Februar 1967

Gerald Moore’s finale

On Monday, in the Royal Festival Hall, Gerald Moore took farewell from the concert platform. Again he displayed the rare range of his pianistic arts, delicate of touch in Schubert’s "Nachtviolen," pungent with its gently chromatic flavours and endearing with close treble harmonies. He was equally felicitous bringing out the cosy humour of "Der Einsame," fingering the semi-quaver turns appreciatively, and revelling, with a witty wink, in the soloist’s jump of a ninth. He modulated as though instinctively to Wolf’s "Kennst du das Land," evoking the feeling of ache and longing as soon as he played the octaves of the song’s postlude of four bars.

Then he rippled the keyboard amiably and epigrammatically during morsels of Rossini and pieces by Mozart. He found the right tone, dark and autumnal for the "Sapphische Ode" of Brahms, and responded swiftly, after the manner born, to the very German coyness of "Vergebliches Ständchen." Not less responsive, Mr Moore was as happily in accord with the milder-piano nuances of Mendelssohn. In all this varied sequence of music, Mr Moore was most sensitively and vocally accompanied by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Victoria de los Angeles and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in turn, sometimes solo, sometimes in conjunction.

The miscellaneous programme was a connoisseur’s delight; evidence of the taste an discrimination of Mr Walter Legge. But the occasion was not one for cold, detached, critical scrutiny; it was a hail and farewell for Mr Moore, who in a half-century’s career has completely transformed the position and function of the piano accompanist. I am not sure that one of Mr Moore’s first concert appearances did not coincide with my first job as a deputy music critic. He "accompanied" some famous performer on the larynx of the period, came on the platform some obsequious distance in the rear of the celebrity, as though by the back-stairs, and didn’t presume to touch the keyboard until he had received, from the soloist, a smile of extreme condescension. He has established his art as a necessary complement to that of any soloist; he has given to it musical and artistic autonomy. With Ivor Newton a worthy pioneer in the same field, he has elevated the "accompanist" to a virtuoso in his own right, just as important as a concert attraction as the next vocalist or fiddler and – more important still – nearly as well paid.

To describe all of this concert’s contributions would end in a miscellany of reportage. A mention of a few of the more memorable moments must suffice. Every time Elisabeth Schwarzkopf sings Wolf’s "Kennst du das Land" – and I am fortunate to be present – I am put under the spell not only of her own highly cultivated art but, also, under the spell of Wolf’s music, so much so that it moves me more than anything else Wolf composed. The song changes Goethe’s marvellous poem to music so apt that it is difficult to think of the poem and music as things separately conceived.

There are, of course, other great settings of the poem; Schubert’s is perhaps truer to the mentality and character of the child Mignon. Wolf’s musical imagination absorbed the poem as though from inside the mind of Goethe, who himself rather transcended the poetic powers of apprehension of his own creation, the haunting, fascinating enigmatically young Mignon.

Admirable, too, was the protean art by which Schwarzkopf conveyed the chilled lonely hopelessness of "Das verlassene Mägdlein"; here Mr Moore’s piano tone was absolutely stone-cold, but intensely poignant. Warmth of art and nature filled the hall when Victoria de los Angeles sang Brahms – "Die Mainacht," "Sapphische Ode," "Von ewiger Liebe," among others – and joined Schwarzkopf in duets of Rossini, including one depicting an affair between two cats. Fischer-Dieskau, liberated from the encircling humours of Falstaff, was in his element singing Schubert; a gorgeous mezza-voce for "Nachtviolen," and good sturdy tone for "Der Einsame."

Space prohibits more than a word for Schwarzkopf and Fischer-Dieskau in duets of Schumann. In any case, it was indeed Gerald Moore’s night. He was, as I say, perfectly accompanied, not the least enthusiastically and importantly by the "sold-out" audience, tickets at top prices.

Neville Cardus

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 23. Februar 1967

G. Moores Abschied

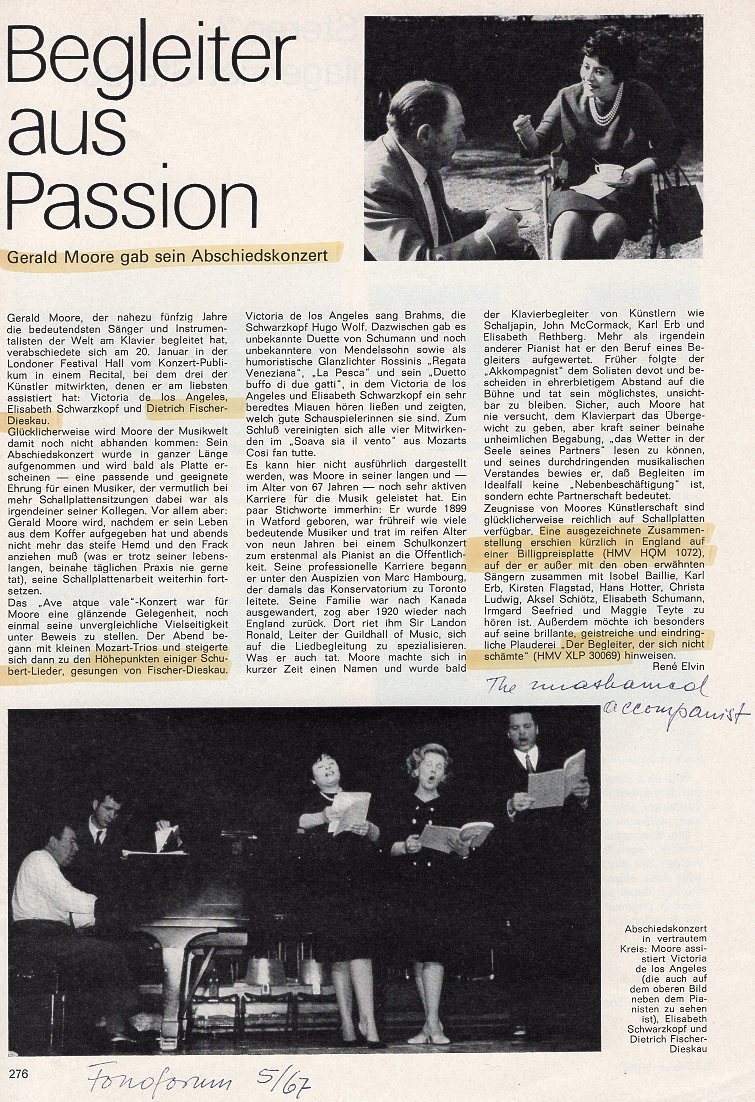

"Gerald Moore hat die so schattenhafte Rolle des Klavierbegleiters bis zum Rang eines gleichwertigen Partners erhoben, des Partners sowohl jener, die mit ihm musizieren, als auch seines Publikums. Ich bin überzeugt, daß es einen dermaßen beliebten und im besten Sinne des Wortes populären Liedbegleiter und Kammermusiker vorher nie gegeben hat und so bald nicht wieder geben wird." Mit diesen Worten hat Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau den international bekannten englischen Musiker geehrt, der nach einer brillanten 50jährigen Laufbahn vom Konzertpodium abtritt.

London hat Gerald Moore in seinem Abschiedskonzert in der bis auf den letzten Platz gefüllten Festival-Halle anhaltende Ovationen gebracht, die auch in der britischen Presse ihr Echo fanden. Spontan erhob sich das Publikum zweimal von seinen Sitzen und beklatschte den Künstler und die drei Sänger des Abends, die zu diesem einmaligen Anlaß zusammengefunden hatten: Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Victoria de los Angeles und Fischer-Dieskau. Ihre Liederprogramme vermochten erneut hinreißendes musikalisches Erlebnis zu vermitteln: Fischer-Dieskau und Moore als Interpreten von Schubert-Liedern, de los Angeles und Moore mit Brahms-Liedern, Schwarzkopf und Moore mit Hugo Wolf.

In seiner Autobiographie "Am I too loud?" (Bin ich zu laut?) hat Gerald Moore Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Victoria de los Angeles und Fischer-Dieskau als die drei Sänger bezeichnet, mit denen er am liebsten zusammengearbeitet habe. Als Elisabeth Schwarzkopf nach dem Krieg darauf bestand, bei den Salzburger Festspielen von dem englischen Pianisten begleitet zu werden, mußte sie österreichischen Musikern gegenüber darauf bestehen, wie sie jetzt erzählte, daß es sich nicht darum handele, Eulen nach Athen zu tragen, sondern eine Oase in die Sahara.

Als Gerald Moore unter Mark Hambourg in Kanada sein Musikstudium begann, war eine solche Partnerschaft zwischen Begleiter und Sänger noch selten. Daß er selbst dazu beigetragen hat, die manchmal recht gespannten Beziehungen auf die Ebene einer gegenseitigen Inspiration zu erheben, ist von ihm auf das größere musikalische Verständnis unter der heutigen Sängerschaft zurückgeführt worden. Frieda Hempel und Schaljapin waren unter den ersten Künstlern, die er bei ihrem Londoner Auftreten begleitete. In den späteren zwanziger Jahren wurde sein Name in der englischen Musikwelt bekannt. Moore wurde, was man von einem Engländer nicht erwartet hatte, zum großen Liederexperten. Friedrich Schorr, Gerhard Hüsch, Alexander Kipnis, Julius Patzak, Elena Gerhardt und Lotte Lehmann waren einige der vielen Sänger, mit denen er überall in der Welt aufgetreten war. Seinen Abschied vom Konzertpodium hat er, nun fast achtundsechzigjährig, mit seiner zunehmenden Nervosität vor jedem Auftreten begründet, doch will Moore sich weiter als Vortragender, Lehrer und in Plattenaufnahmen betätigen.

rjh

Die Welt, 30. März 1967

Dank an einen Begleiter

Gerald Moore tritt ab – Mozarts "Lucio Silla" – Londoner Musikbrief

Wenn ein Klavierbegleiter, und sei er noch so beliebt, seinen Abschied vom Podium nimmt, so geschieht das meist ohne Aufhebens. Nicht so im Lande der klassischen Heldenverehrung, wo das "Farewell"-Konzert ein guter Brauch ist. Besonders wenn es sich um einen Musiker wie Gerald Moore handelt, der dreißig Jahre lang seinen Sängern ein unvergleichlicher Sekundant war. Moore ist aus unzähligen Konzerten und aus Hunderten von Schallplatten bekannt. Das Schlußkonzert seiner aktiven Laufbahn wurde zu einer einzigartigen Demonstration, die von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Victoria de los Angeles und Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau bestritten wurde.

Das Programm, eine Art Hausmusik, war bewußt auf Werke abgestellt, die an die Kunst des Begleitens höchste Anforderungen stellen, gleichzeitig aber auch den intimen Charakter der Veranstaltung betonen. Und so hörte man Lieder, Duette und Terzette, denen man sonst im Konzertsaal kaum begegnet – schon gar nicht in der Londoner Festival Hall.

Es gab Duette von Schumann und Mendelssohn, Terzette von Haydn und Mozart, in denen die Soprane über dem sonoren Bariton hochwirbelten, und als besonderen Leckerbissen die venetianischen Duos von Rossini, darunter das bezaubernde Katzenduett, dessen Text lediglich aus dem Wort "Miau" besteht. Der Jubel des ausverkauften Saales und der Beifall des getreuen Publikums fanden einen würdigen Abschluß mit den Anfangstakten des Schubert-Liedes "An die Musik", das, von Moores Hand aufgenommen, seit vielen Jahren die Einleitung zu dem wichtigsten Musikprogramm der BBC, "Music Magazine", bildet.

[...]

Autor unbekannt

Zeitung und Datum unbekannt

Pianisten

Nach dir

Die Musik war von Haydn, der Text extemporiert. "Oh, wollte Gerald nur weiterspielen", sangen Victoria de los Angeles, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf und Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Sie wehklagten zum Ruhm ihres Mannes am Klavier.

Denn Gerald Moore, 67, der "Prinz", "König", "Toscanini" aller Begleiter spielt nicht mehr weiter. In der Londoner Royal Festival Hall gab er jetzt seinen Abschiedsabend. Er begleitete seine drei Lieblingsstars zum allerletzten Mal.

Moore, der rundliche, rotbäckige Pianist, bei London geboren, in Kanada aufgewachsen, hat in mehr als fünfzig Jahren seiner Konzertsaalkarriere mit vielen der größten Musiker zusammengearbeitet – mit Elena Gerhardt, Lotte Lehmann, Elisabeth Schumann, Kathleen Ferrier, mit Schaljapin, John Mc Cormack, Yehudi Menuhin, Pablo Casals und immer wieder mit Fischer-Dieskau und Hermann Prey.

Obwohl er immer nur als zweiter Mann aufs Podium trat, hatte er allemal eine hohe Meinung von seiner Kunst. "Als ich ein junger Mann war", so erinnerte er sich, "wollten die Sänger nur eine Art Löschblatt, das ihre Wünsche aufsaugte. Ich halte jedoch nichts von zaghaften Begleitern. Auf den Begleiter fällt die halbe Verantwortung, wenn auch nicht die halbe Gage." Und er bekannte: "Es gibt für mich nichts Schöneres, als zusammen mit einem guten Sänger die ‚Winterreise’ zu interpretieren. Selbst wenn ich über die Virtuosität eines Artur Rubinstein verfügte, würde ich immer noch lieber Begleiter bleiben."

An Virtuosität ließ es der britische Spezialist für Hugo-Wolf-, Brahms- und Schubert-Lieder dennoch nie mangeln. Moore, lobte Freund Fischer-Dieskau, habe "die so schattenhafte Rolle des Klavierbegleiters zum Range eines gleichwertigen Partners erhoben". Als ebenbürtiger Partner war er denn auch überall begehrt, in Australien, Amerika und der Sowjet-Union, auf den Festivals von Salzburg und Granada. An Ruhm und Popularität, soviel ist sicher, kann es Moore mit jedem Klavier- oder Geigensolisten aufnehmen. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau zumindest ist "überzeugt, daß es einen dermaßen beliebten Liedbegleiter und Kammermusiker vorher nie gegeben hat und so bald nicht mehr geben wird".

Nun jedoch ist der englische Liederspezialist Gerald Moore, Autor "Freimütiger Bekenntnisse eines Begleiters" und einer Autobiographie ("Bin ich zu laut?"), den Strapazen seines Pianistendaseins nicht mehr gewachsen. Er will künftig nur noch als Lehrer, Vortragsreisender und Schallplattenkünstler wirken.

Als Moore in der Royal Festival Hall seinen letzten Liederabend absolviert hatte, erhoben sich – seltene Hommage – dreitausend Zuhörer und applaudierten im Stehen. Fischer-Dieskau ließ ihm beim Abgang den Vortritt: "Diesmal, Gerald, nach dir."

Nach der anschließenden Sektparty brachte Moore ("Ich weiß nicht recht, ist das nun eine Hochzeit oder eine Beerdigung?") mit Ehefrau Enid seine Begleiterkarriere vollends zum Abschluß: Beide sammelten sämtliche Blumensträuße in dem mit Blumen überladenen Hotelzimmer ein und warfen sie ungeniert in die Badewanne.

Moore: "Dieser Abschnitt meines Lebens ist jetzt vorüber."

Autor unbekannt